It's always a rather awe-inspiring moment when a poem escapes the clutches of the poet and takes on a life of its own, beyond the creator. A few days ago I had the honour of hearing my poem For Your Eldorado read out at a packed concert in celebration of a great songwriter, social chronicler, and one of the first people ever to champion my own writing.

In his inimitable, quiet way, Graeme Miles is something of a local legend in the north-east of England. In a period of just over 20 years spanning the 1950s and 60s, he wrote 300-odd songs chronicling the landscape and the changing way of life in the Teesside where he grew up, lived and worked. A disciple of the Folk Revival, Graeme's songwriting was heavily influenced by the traditional music of the area. Many of his songs are shared and passed around Teesside today as if they were true folk songs, or nursery rhymes.

Graeme Miles passed away earlier this year without ever becoming a mainstream name in the arts world. He'd never have wanted such recognition. He was humble, dignified and self-effacing. For Graeme, the created work mattered far more than the creator. When traditional ways of life were coming to an end, and changing economic fortunes were dealing hammer-blows to the established industry of the region, Graeme saw his songs as his contribution to a shared heritage, a collective memory capable of withstanding the changes all around.

I had the great privilege of getting to know Graeme very early in my journey as a poet. Some fifteen years ago, I became a member of Jackdaw, an informal little poetry circle in Durham, which was attended by Graeme and his artistic collaborator Robin Dale. Graeme was the quiet member of the group, but his creativity was clear from the start. He was an aspiring poet, striving to write “good, bad and indifferent verse, but not necessarily in that order” (his words). He produced a series of wonderful illustrations for the first Jackdaw anthology (including the magnificent cover picture that graces this article). And it was through Robin's haunting performances of Graeme's songs that I first got to know his incredible back catalogue. Pastoral poems, work songs, chronicles of changing times: it seemed Graeme had written them all.

I had no idea how far Graeme's music had travelled until I started to venture into the idiosyncratic world of the region's folk clubs. It was a surprise to me just how many musicians – from fireside amateurs to bona-fide, touring professionals – had Graeme's songs in their repertoire. They had a natural home in north-east England, but many were known across the length of the UK (and even beyond; another exponent, Martyn Wyndham-Read, has exported the Graeme Miles songbook all the way to Australia!). I once heard Bob Fox sing The Shores of Old Blighty to a field of 10,000 people at the Cropredy Festival – and most of those 10,000 joined in the refrain.

What makes Graeme's songs special isn't just their role as sociological record. These are songs with immense heart: poems-set-to-music which are filled with love and loss, dreams of peace and hope for a better tomorrow. As a writer, Graeme was always among the people. He took on back-breaking manual labour in order to celebrate the labourers in song. He slept rough in the bitter winter of 1963. He walked the long march from Aldermaston with the original Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. His songwriting was political, but not in any contrived or self-important way. His depiction of the wind across the North York Moors in Horumarye may have been intended to salute the timeless pilgrims of the Lyke Wake Walk; but when he sang “Cold blows the wind over Fylingdales”, it was impossible for a listener not to form a mental image of the frightening outpost of Cold War paranoia that dominated the landscape in Graeme's own lifetime. He could discuss world peace in grand allegory in The Eagle and the Dove, or through the simple dreams of a conscripted squaddie wishing for The Shores of Old Blighty.

I didn't know it at the time, but Graeme had known his share of romance, and romance gone wrong, in his younger days too. His first love song – the enigmatically titled Exercise no. 77 (only recently re-catalogued as the much more poetic Amouret) – is one of the finest pieces of romantic poetry I know. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that Graeme and I first became friends. At a turbulent time in my own private life, Graeme understood the subtext in my poetry, and encouraged me not to be afraid to express what I was feeling. He even illustrated a couple of those early attempts.

And this is where I owe Graeme a real debt. I'd only been writing poetry a couple of years when I joined the Jackdaws. But very early on, Graeme found a point of connection with my writing, and became a generous champion. I was still far from the point of actually submitting my work for publication; but it's in no small measure down to the confidence that Graeme always placed in me and my writing, that I was eventually able to do so. Perhaps it was because we shared subject matter – the natural world, love and heartbreak, occasional political comment. More likely, it was just because he was a generous, thoughtful man, keen to nurture creativity wherever he found it. He was scathing in his dismissal of the fake and the superficial. But when he found something genuine, he was passionate in his nurturing of it.

Graeme and I corresponded for several years after I left Durham, and gradually became what I hesitatingly describe as “a serious poet”. One of my most treasured possessions is the signed copy of Songscapes, his first published volume of songs, which he gave to Kath and me as a wedding present. I've watched – admittedly at a distance, but with pride and delight – as Graeme's work has attracted serious recognition (notably from the English Folk Dance and Song Society) and new generations of musicians have declared their allegiance. The Unthanks, the master reinterpreters of north-eastern traditional music, and up-and-coming rabble-rousers The Young 'Uns, are just two of the bands who have found inspiration from Graeme's work and his outlook on his art.

News of Graeme's death earlier this year was, of course, a great sadness. But it was a fitting tribute to the man and his music that his devotees were able to fill Cecil Sharp House on 23rd November for a celebration of Graeme's legacy. The Unthanks, The Wilsons, Martyn Wyndham-Read, The Young 'Uns and even Robin Dale performed a wondrous mix from the vast Graeme Miles repertoire, from the simple solo voice (Robin's haunting rendition of Exercise no. 77 still sends shivers through me) to avant-garde arrangements with brass, fiddle and sample loops of Graeme's own voice reading his poetry.

My poem, For Your Eldorado, played a small part in the proceedings. Written in 2008, and taking its title from one of Graeme's best loved songs, the poem was my thank-you for his wonderful music and for the encouragement and inspiration over the years. By a circuitous route, the poem had managed to find its way into the hands of Martyn Wyndham-Read, who judged it fitting to be shared during the evening, and contacted me out of the blue to ask for permission for it to be read out.

I probably won't ever know what Graeme thought of the poem. I sent him a copy, back when it was fresh off the printer, but we had already lost touch by this point, and I didn't get a reply. I hope he appreciated it. For now, it stands as my tribute to a generous hearted, intelligent, wise and creative writer, and a gentleman of the first order. For me, Graeme Miles was and is a poet among poets. If my creative work can in some small measure live up to the example he has set, then I’ll be a very proud man indeed.

(All illustrations in this article are by Graeme Miles and appeared in the Jackdaw writers' anthology in 2000. The text of my poem For Your Eldorado can be found at http://www.graememiles.com/lyrics.)

(For more about Graeme and his music, visit http://www.graememiles.com)

Thursday, 28 November 2013

Sunday, 27 October 2013

The Poetry Society: 6 months in

Regular readers of the Soapbox will remember that earlier this year I joined the Poetry Society. I've always had misgivings about this particular organisation, and promised to keep Soapbox readers updated on whether or not I got my money's worth from being a member. 6 months into my membership, I think it's time to assess the state of the union.

What have I got from the Poetry Society so far? And what’s missing?

The first sign that I was a bona fide Poetry Society member was the issue of Poetry News that dropped through my letterbox back in February. The Society's broadsheet comes out four times a year and is Society members' window on the work the Society does nationally as an advocate for the art of poetry.

As a news sheet, it has strengths and weaknesses. Coverage of the death of Seamus Heaney, as you might expect, was thorough, sensitive and had suitable gravitas to it. But the Society seems a little selective as to what it considers ‘news’: the plagiarism scandals, for instance, haven't merited a footnote.

I was half tempted to go through my first issue, circle every unfamiliar word in red ink, and write a blog article headed “Words I didn't understand in Poetry News.” There were a lot of them – and this bothered me.

Like many poets, I'm largely self-taught. My academic schooling in poetry culminated in O-level English Literature, and what knowledge I've acquired since has been entirely from reading poems myself and talking about them, or reading about them in the journals and websites that I follow. I don't have the luxury of a literature degree or a creative writing qualification. One of the most important things a group like the Poetry Society should do is educate its members. It shouldn't assume that its members are already experts and that it doesn't need to explain what it is talking about.

Happily, I've had no difficulty understanding subsequent editions of Poetry News. And I have learned stuff about poets, and poems, that I didn't know before.

Poetry Review, the Society's journal, is a different kettle of fish. Among my literary friends, it has a reputation for being mainly interested in intellectual, ‘difficult’ poetry. I have to admit that the poems so far haven't been anything like as ‘difficult’ as I was expecting. But for the most part it is the articles about poetry that I've found far more interesting, and which for me justify the existence of the magazine. These, and the National Poetry Competition winners, which are reproduced in full and discussed in detail, giving first-rate insight into the workings of one of the biggest poetry competitions in the UK.

The Society was given a human face when I decided to join our regional group, or Stanza. This meets once a month in York to critique poems, and organises occasional events to raise the profile of our local poets. Our Stanza rep, the indefatigable Carole Bromley, runs the monthly critique sessions. She's a natural, thoughtful hostess and I very much appreciate the effort she put into making me welcome as a new Stanza member. She’s also an excellent critique group leader, with an “iron-fist-in-velvet-glove” approach that makes the sessions fast-paced, lively, and very high quality.

It was a huge privilege for me to be invited to join the York Stanza poets at their recent showcase at the Ilkley Literature Festival Fringe. As a newcomer, I could very easily have been passed over in favour of better established names. But this is a truly egalitarian group; my brief membership was no barrier to me taking part alongside everybody else. There were 10 of us performing on the night, in the end; just a 5-6 minute slot each, but I was in the company of poets who have made regular appearances on the prize winners' lists for the Bridport, the Keats-Shelley and other ‘premier league’ poetry competitions. It's a real tribute to the success of the Stanza that I was allowed to feel I had every right to be standing up there in such august company, even if I doubted it myself occasionally!

Now that I have a book of my own to tout, the literary life is all about networking. This should be something that the Poetry Society can facilitate better than anybody. The Stanza, of course, is a great place to get to know poets who are at the top of their game, to share ideas and inspiration and to help me work towards the distant goal of Poetry Collection No. 2. But if it weren't for the Stanza, I have say that the Society is giving me no help at all with the networking I need to do to get myself established as a poet. That's despite the promises that it will host member profiles on its website, showcase members' books, give us opportunities to take part in national events, etc. All such enquiries I've made so far have come to naught. In fact, my emails to the Society don't even get a reply.

So I guess the jury's still out as to whether the Society is worth it. At the moment, I'd suggest probably yes, but that's purely because of the Stanza and the opportunities it has afforded me (which are as much down to Carole herself as the Poetry Society). Other than that, I get the feeling that the Society isn't all that interested in me. And that's a real shame.

It's another 6 months before my membership comes up for renewal. If the Society can convince me in that time that it isn't only interested in the academic, the highbrow and the London-centric, then I'll be only too happy to renew. But I'll be honest. It's still got a bit of a hill to climb.

Saturday, 28 September 2013

Where have all the war poets gone? Part 1

My friend and poetic sparring partner Tim Ellis sparked off yet another cracking Facebook debate a couple of weeks ago. In a discussion of his e-book On the Verge – an elaborate satire on the Western world's disregard for the consequences of environmental degradation – he asked the question: why were there so few poets writing about climate change? Are we afraid to tackle the subject? Or are we more comfortable disregarding the issue altogether, and writing about ‘safe’ subjects like love, daffodils and cats – thus proving the truism that most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people?

Tim has a point. Very few of the poets I know in Yorkshire are writing about climate change – or Syria, homelessness or benefit cuts. Those few that are overtly engaging with these issues seem to be writing rants, rather than poems – shouty tirades that fail to have any real impact. The bona fide poems are conspicuous by their absence.

I felt duty bound to play devil's advocate. It wasn't, I protested, that we didn't want to write about such things. The difficulty is that for most of us, war and homelessness and climate change are subjects too big to write about. Is it even worth the poet's effort trying to write about such things, when any given 30-second run of newsreel images makes our months of laboured word-craft pale into insignificance? Isn't it better to write about love, and daffodils, and cats, because these things at least give us a moment's escape from the ugly realities of the world?

I don't really believe this theory. Poetry is the stuff of human life. Poets, as a class, have a sort of responsibility to humanity, to reflect and recount all of human life. We need poets who write about climate change, and war, just as much as we need poets who write about love (or cats). Poets, collectively, are failing the world if we decide that any subject is not fitting subject matter to write poetry about.

So why do so many of us find it so hard to write poems about ‘big issues’ – or make such a bad job of it when we do try?

War and climate change are pretty unsubtle things. So there is a tendency, when addressing them head-on, to think that ‘subtle’ isn’t good enough. Why write a sonnet, when you can have a rant instead? But rants on their own are an artform more akin to Party Political Broadcasts than to poems. I'm not saying they don't have their place. Someone needs to get up on the barricades and say what the rest of us are feeling. But it doesn't require poetry to do that. Rhetoric, yes. Oratory, probably. But poetry? The subtlety of poetry is just going to be lost on an angry mob.

So what can poetry do to illuminate, inform and educate about the big issues?

In my opinion, poetry has two qualities that newsreel footage and mob rants don't have. Firstly, poetry is a way of looking slant-wise at the world – of finding meanings and connections that we never realised were there. By looking at something slant-wise, we end up looking at it more deeply – understanding its inner workings, its relationship to the wider environment. We find the new angle that the news reporters and the propagandists miss.

Pete Seeger's Where have All the Flowers Gone? is a prime example. One of the greatest anti-war songs ever written; but it never goes near a battlefield. Its starting-point is the cycle of life and love, as young girls pick flowers to be reminded of their sweethearts. It ends up in the graveyard where all their sweethearts are buried, without us quite noticing how we got there – and then the whole futile cycle starts again.

The second thing that poetry does is to use the microcosm to tell us about the macrocosm. A war poem doesn't tell us about ‘war’ – ‘war’ is too big, too abstract and too grotesque a concept to be pinned down in a 14-line sonnet. But a Wilfred Owen poem can tell us about a single, heart-stopping moment of terror in the life of a single soldier. And it's when we grasp the notion that this awful moment was replicated tens of thousands of times over, in the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, that we begin to feel the true horror of the war. When we see its discarded left-overs picked over by the ragmen in Patricia McCarthy’s Clothes that Escaped the Great War – the 2012 winner of the National Poetry Competition – those of us who have been fortunate never to have experienced such desolation can at least begin to grasp the awful emptiness, the futility of what was left behind.

There is an even subtler way that poets can be war poets, or climate change poets. A good poem has many layers. The subtext of a poem often carries a meaning that goes far beyond the subject matter in the written words. Love poets (and love-gone-wrong poets) use subtext all the time, to turn a physical description into an emotional map of the human heart. A whole generation of literature students are currently writing theses on the existential significance of William Carlos Williams' wheelbarrow. So what's to stop a poem about a love affair, a cat, or even a daffodil, also being an unwritten commentary on the folly of war, or the depredations of global warming? All it takes is for poets to be made aware of the possibilities.

Tuesday, 17 September 2013

Are we all plagiarists now?

Is it just me, or do the poetry plagiarism scandals seem to be getting too close for comfort?

I was shocked when I read the allegations by Carcanet poet Matthew Welton that his work had been plagiarised by his fellow Nottingham poet CJ Allen. All of the plagiarism revelations to date have been scandalous, but this one seemed to hit home in a more – well, personal way. After all, I've entered competitions where CJ Allen has been a prize winner.

I must be clear: at the time of writing there is no suggestion that ANY of CJ Allen's prize winning work is anything other than his own original creation. But sadly, now that he's been tarnished with the plagiarist’s brush I can't avoid a nagging little “What if...?” that creeps into my mind when I hear his name mentioned. And it's depressing that I should think about any poet that way, particularly not one with such a strong track record and hitherto good reputation. If I start doubting one poet, how long before I start doubting them all?

What makes it worse is I have a sneaking suspicion that very few poets are entirely blameless when it comes to appropriating other people's work.

We all absorb ideas and images from the world around us. Writers pilfer constantly from overheard conversations, bits of pop culture, lyrics, advertising jingles, politicians' soundbites, and the like. “Intertextuality”, where a piece of writing knowingly references an existing source from the print or broadcast media, is one of the buzz-words in contemporary poetry. If, like me, you go to a lot of poetry readings and open mics, you'll be exposed to a whole barrage of poetic phrases, unusual metaphors and similes, and the like. And the chances are you may be picking them up subconsciously, reworking and reusing them in your own creative work.

I realised – and realised in a very public arena – that this was happening to me too, not so long ago. I'd been working on a new poem, a childhood reminiscence infused with my beloved fairytale imagery. I had a line in my head, which provided a perfect ending for the poem. And I knew it wasn't entirely ‘my’ line. I'd picked it up from somewhere – but where, I had absolutely no idea. Was it something I'd read in one of my books of fairy-stories? After all, I often find ideas for poems lurking within their covers. Had I heard it on TV, or the radio? Or – and this is the tricky bit – was it another poet's line, that I'd heard at a reading or an open mic, and picked up without realising that I'd done so?

It turned out to be the latter. This perfect final line for my new poem was somebody else's work. I used it in the poem. And the moment I realised where I'd heard the line before was the moment I read it out loud to an audience – at the self-same open mic that I'd first heard it, several months earlier.

Urgh.

If the poet who had created that line had been present, I could easily have ended up tarred with the same brush as CJ Allen. They weren't, as it turned out. But I had no idea who had written that line; all I knew was it was someone who might well be in the room, who almost certainly had friends who were in the room. The only honourable thing to do was to make a public confession of what had happened, and ask the original poet’s forbearance on the grounds that imitation, in this case, really was the sincerest form of flattery.

The audience at that open mic are a lovely lot. They were very understanding. They actually applauded the poem (and the confession) – and they didn't come after me with pitchforks afterwards, or ‘out’ me on the Carcanet blog. But I know fine well that I now have no right to use that ‘borrowed’ line in my poem. I could never be comfortable, submitting it for publication in the knowledge that the poem owed its power to someone else's words.

That last line has now been binned. It took me a couple of weeks to come up with the replacement (which is not nearly as good as its ‘borrowed’ predecessor). But such is life. All poets tend to find that, just when we want to say something really profound, someone else has got there before us. We shrug our shoulders, revise our poems, and move on.

The whole experience has made me realise just how close all poets come, at times, to being plagiarists. After all, we'd have precious little source material if we had to rely only on the original stuff that comes out of our heads. But the stuff we pick up from our environment – the lyrics, the headlines, the discarded soundbites – these are someone's creative work too. And the fine line between unconsciously using these as the starting-point for our creative process, and rehashing them wholesale as if they belonged to us in the first place, is finer than most of us realise.

I was shocked when I read the allegations by Carcanet poet Matthew Welton that his work had been plagiarised by his fellow Nottingham poet CJ Allen. All of the plagiarism revelations to date have been scandalous, but this one seemed to hit home in a more – well, personal way. After all, I've entered competitions where CJ Allen has been a prize winner.

I must be clear: at the time of writing there is no suggestion that ANY of CJ Allen's prize winning work is anything other than his own original creation. But sadly, now that he's been tarnished with the plagiarist’s brush I can't avoid a nagging little “What if...?” that creeps into my mind when I hear his name mentioned. And it's depressing that I should think about any poet that way, particularly not one with such a strong track record and hitherto good reputation. If I start doubting one poet, how long before I start doubting them all?

What makes it worse is I have a sneaking suspicion that very few poets are entirely blameless when it comes to appropriating other people's work.

We all absorb ideas and images from the world around us. Writers pilfer constantly from overheard conversations, bits of pop culture, lyrics, advertising jingles, politicians' soundbites, and the like. “Intertextuality”, where a piece of writing knowingly references an existing source from the print or broadcast media, is one of the buzz-words in contemporary poetry. If, like me, you go to a lot of poetry readings and open mics, you'll be exposed to a whole barrage of poetic phrases, unusual metaphors and similes, and the like. And the chances are you may be picking them up subconsciously, reworking and reusing them in your own creative work.

I realised – and realised in a very public arena – that this was happening to me too, not so long ago. I'd been working on a new poem, a childhood reminiscence infused with my beloved fairytale imagery. I had a line in my head, which provided a perfect ending for the poem. And I knew it wasn't entirely ‘my’ line. I'd picked it up from somewhere – but where, I had absolutely no idea. Was it something I'd read in one of my books of fairy-stories? After all, I often find ideas for poems lurking within their covers. Had I heard it on TV, or the radio? Or – and this is the tricky bit – was it another poet's line, that I'd heard at a reading or an open mic, and picked up without realising that I'd done so?

It turned out to be the latter. This perfect final line for my new poem was somebody else's work. I used it in the poem. And the moment I realised where I'd heard the line before was the moment I read it out loud to an audience – at the self-same open mic that I'd first heard it, several months earlier.

Urgh.

If the poet who had created that line had been present, I could easily have ended up tarred with the same brush as CJ Allen. They weren't, as it turned out. But I had no idea who had written that line; all I knew was it was someone who might well be in the room, who almost certainly had friends who were in the room. The only honourable thing to do was to make a public confession of what had happened, and ask the original poet’s forbearance on the grounds that imitation, in this case, really was the sincerest form of flattery.

The audience at that open mic are a lovely lot. They were very understanding. They actually applauded the poem (and the confession) – and they didn't come after me with pitchforks afterwards, or ‘out’ me on the Carcanet blog. But I know fine well that I now have no right to use that ‘borrowed’ line in my poem. I could never be comfortable, submitting it for publication in the knowledge that the poem owed its power to someone else's words.

That last line has now been binned. It took me a couple of weeks to come up with the replacement (which is not nearly as good as its ‘borrowed’ predecessor). But such is life. All poets tend to find that, just when we want to say something really profound, someone else has got there before us. We shrug our shoulders, revise our poems, and move on.

The whole experience has made me realise just how close all poets come, at times, to being plagiarists. After all, we'd have precious little source material if we had to rely only on the original stuff that comes out of our heads. But the stuff we pick up from our environment – the lyrics, the headlines, the discarded soundbites – these are someone's creative work too. And the fine line between unconsciously using these as the starting-point for our creative process, and rehashing them wholesale as if they belonged to us in the first place, is finer than most of us realise.

Saturday, 31 August 2013

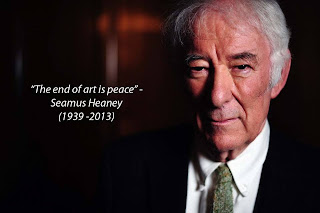

Seamus Heaney: RIP

I don't think my meagre words can add very much to the many tributes that people far more erudite than I have paid to Ireland's most prominent poet since Yeats. I was lucky enough to hear the great man reading at York University just a couple of months ago; and it was an extraordinary experience.

Some poets are performers. They accompany their words with dramatic and flamboyant gestures, music, rhythm, sound effects, or multi-media installations. I have huge respect for those that can do this well. But there is something uniquely awe-inspiring about the quiet simplicity of a single poet reading their words, without embellishment, to a still, rapt audience.

That is my defining memory of Seamus. That, and his self-deprecating answer to the questioner who told him "By brother says that your work can be summed up in the words 'death and potatoes' - how would you describe it?" He simply smiled, and told the questioner that he couldn't describe his work any better.

My final comment on the loss of Seamus Heaney is a wry tribute from the Yahoo! news page which reported his death. A commentator with the alias "Taylor Swift Rules" had made a disparaging remark about how this was typical of Yahoo!, advertising the death of "someone nobody has ever heard of." There's a thesis that could be written about what a sad state of affairs it is that there are English-speaking people who haven't heard of Seamus Heaney. But the best riposte was the one from the wag who replied, "Who's Taylor Swift?"

(photo taken from Wexford Festival Opera)

Some poets are performers. They accompany their words with dramatic and flamboyant gestures, music, rhythm, sound effects, or multi-media installations. I have huge respect for those that can do this well. But there is something uniquely awe-inspiring about the quiet simplicity of a single poet reading their words, without embellishment, to a still, rapt audience.

That is my defining memory of Seamus. That, and his self-deprecating answer to the questioner who told him "By brother says that your work can be summed up in the words 'death and potatoes' - how would you describe it?" He simply smiled, and told the questioner that he couldn't describe his work any better.

My final comment on the loss of Seamus Heaney is a wry tribute from the Yahoo! news page which reported his death. A commentator with the alias "Taylor Swift Rules" had made a disparaging remark about how this was typical of Yahoo!, advertising the death of "someone nobody has ever heard of." There's a thesis that could be written about what a sad state of affairs it is that there are English-speaking people who haven't heard of Seamus Heaney. But the best riposte was the one from the wag who replied, "Who's Taylor Swift?"

(photo taken from Wexford Festival Opera)

Friday, 26 July 2013

Would you just look at what the Arts Council is doing with our money now...

Two identical envelopes dropped through my door yesterday. One addressed to “Andy Humphrey – Freelance Writer”; one to “The Chairman”. Both of them contained the same thing. A single piece of red card, mocked up with the imprint of a button that said “Push”. On the other side, a cursory blurb announcing “New Work from the Writing Squad – supported by Arts Council England.” And that was it.

Excuse me, but am I missing something here? I don’t completely oppose the idea of unsolicited mail (I have to send it myself, from time to time, when promoting competitions or touting for new business). But when I get unsolicited mail I appreciate it if, at the very least, it makes some effort to tell me WHAT THE HELL IT IS ABOUT. This prime candidate for the recycling bin told me nothing about who the Writing Squad are, or why I should care. It said nothing about what kind of new writing it was promoting – it just gave me a cursory web address as if it was implicit that the answer to all my longings would be there. Nor, and this is the bit that REALLY gets my goat, did it say why on earth this had merited Arts Council funding, when other truly worthy projects that I know of are repeatedly getting turned down.

OK, maybe the sender was presuming a bit of prior knowledge on my part. It’s not inconceivable that maybe I ought to know who the Writing Squad are, or why it matters that they are producing new writing. But if they are trying to tout for new business, oughtn’t they to do me the courtesy of doing a little bit of the work for me? Like sending me a press release, an excerpt of some of this great new writing – or even (and wouldn’t this be marvellous?) an invitation to get involved? But no. There was none of that. Just a bit of gimmicky red card.

No doubt this was the product of some head-in-the-clouds marketing guru’s blue-skies, high-concept, outside-the-box publicity machine. But to me it really just seemed as if the Writing Squad, whoever they are, couldn’t be bothered. They didn’t want to tell me who they are, how great they are, or what they have to offer me. After all, why go to all the hard work of scripting a press release when the Arts Council will give you money to print crappy bits of red card instead?

And so to the question: did the Arts Council know that this is what their money was going to be spent on? And if they did, who on earth had the idea that this was a sensible way to spend taxpayers’ money? Arts Council money, after all, is public money, paid in by British taxpayers – people like me.

I’d like to know how many people across the country this has been sent to. I’ve been sent two, after all – which means two envelopes, two lots of postage costs. Even if they confined their mailing to all the freelance writers and writers’ groups in Yorkshire, at the very least that’s a few hundred quid of their grant spent already. If the damn things have gone nationwide, we’re talking a cost of thousands. Just think what that money could have been spent on. Community arts initiatives – I know of projects in the north-east, designed as outreach to socially excluded groups, which haven’t been able to get any funding in the last few years. Brilliant multi-media shows combining spoken word with music, visual art and storytelling, that can’t go on tour to wider audiences because the Arts Council won’t fund the costs of a tour. Journals forced to close because the grants on which they depend have not been renewed. And what are they giving money to instead? THIS rubbish.

I suppose I should congratulate the Writing Squad. If they’ve done nothing else, they’ve made me talk about them, and apparently there’s no such thing as bad publicity. But it’s the Arts Council who should be shamed by this flagrant waste of public money. To deny grants to grassroots arts initiatives in deprived communities is bad enough. But to allow our money to be used for this experiment in third-rate, yuppie ad-agency tosh is, frankly, unforgiveable.

Excuse me, but am I missing something here? I don’t completely oppose the idea of unsolicited mail (I have to send it myself, from time to time, when promoting competitions or touting for new business). But when I get unsolicited mail I appreciate it if, at the very least, it makes some effort to tell me WHAT THE HELL IT IS ABOUT. This prime candidate for the recycling bin told me nothing about who the Writing Squad are, or why I should care. It said nothing about what kind of new writing it was promoting – it just gave me a cursory web address as if it was implicit that the answer to all my longings would be there. Nor, and this is the bit that REALLY gets my goat, did it say why on earth this had merited Arts Council funding, when other truly worthy projects that I know of are repeatedly getting turned down.

OK, maybe the sender was presuming a bit of prior knowledge on my part. It’s not inconceivable that maybe I ought to know who the Writing Squad are, or why it matters that they are producing new writing. But if they are trying to tout for new business, oughtn’t they to do me the courtesy of doing a little bit of the work for me? Like sending me a press release, an excerpt of some of this great new writing – or even (and wouldn’t this be marvellous?) an invitation to get involved? But no. There was none of that. Just a bit of gimmicky red card.

No doubt this was the product of some head-in-the-clouds marketing guru’s blue-skies, high-concept, outside-the-box publicity machine. But to me it really just seemed as if the Writing Squad, whoever they are, couldn’t be bothered. They didn’t want to tell me who they are, how great they are, or what they have to offer me. After all, why go to all the hard work of scripting a press release when the Arts Council will give you money to print crappy bits of red card instead?

And so to the question: did the Arts Council know that this is what their money was going to be spent on? And if they did, who on earth had the idea that this was a sensible way to spend taxpayers’ money? Arts Council money, after all, is public money, paid in by British taxpayers – people like me.

I’d like to know how many people across the country this has been sent to. I’ve been sent two, after all – which means two envelopes, two lots of postage costs. Even if they confined their mailing to all the freelance writers and writers’ groups in Yorkshire, at the very least that’s a few hundred quid of their grant spent already. If the damn things have gone nationwide, we’re talking a cost of thousands. Just think what that money could have been spent on. Community arts initiatives – I know of projects in the north-east, designed as outreach to socially excluded groups, which haven’t been able to get any funding in the last few years. Brilliant multi-media shows combining spoken word with music, visual art and storytelling, that can’t go on tour to wider audiences because the Arts Council won’t fund the costs of a tour. Journals forced to close because the grants on which they depend have not been renewed. And what are they giving money to instead? THIS rubbish.

I suppose I should congratulate the Writing Squad. If they’ve done nothing else, they’ve made me talk about them, and apparently there’s no such thing as bad publicity. But it’s the Arts Council who should be shamed by this flagrant waste of public money. To deny grants to grassroots arts initiatives in deprived communities is bad enough. But to allow our money to be used for this experiment in third-rate, yuppie ad-agency tosh is, frankly, unforgiveable.

Thursday, 20 June 2013

Plagiarism - what can we do about it?

The high-profile plagiarism scandals of recent months can't have gone unnoticed by the editors of top literary journals or the organisers of poetry competitions. With two serial plagiarists unmasked recently, many editors must be asking themselves if this is just the tip of the iceberg. What if those brilliant, original, prize-winning poems aren't original after all? What if someone just happens to have nicked them from somebody else's website, or from a forgotten poetry collection published 30 or 40 years ago?

There must be more than a suspicion that the plagiarism scandal calls into question the whole existence of poetry competitions. When a brilliant, unknown poet appears from nowhere to walk off with several hundred pounds' worth of prize money, some are bound to look askance on the winner and wonder just how original they really are. Are they just passing off the work of forgotten writers from a generation earlier? There are certainly rumblings that some competition organisers are going to start looking with new suspicion on ‘unrecognised’ names who achieve competition success.

To me, this is a dangerous mindset. After all, the whole point of poetry competitions is to give the brilliant unknowns a chance to make their mark, on a level playing field when up against established names. That's why poetry competitions are judged anonymously – so there's no chance of a judge being influenced by an entrant's reputation, or lack of one.

There are already competitions which churn out the same ‘type’ of winner, year after year with tedious predictability – often a winner who turns out to be a well established name on the poetry scene, frequently someone with several collections to their name. It's almost as if the judges only want work from a particular school of thought or writing. It would be depressing indeed if those competitions which still champion the independent voice are put in a position where they can no longer do so. Small competitions don't have the funds to defend lawsuits, and can't afford the reputational damage that might ensue if their champion work turns out to have been a plagiarised product. Will these competitions close altogether, rather than run the risk?

I'm a competition judge myself. I certainly don't want to be in the embarrassing position of mistaking a plagiarised poem for a brand new piece of original writing. But it could happen, even to the best of us. The sad fact is that many poets of the last hundred years have published their collections and then vanished without trace – and there's nothing to stop an opportunist taking advantage of the words they left behind them. Not even the best read judge is going to be able to recognise every plagiarised work for what it really is.

However, there's just the possibility that the recent scandals are signs that the situation is getting better, not worse. Serial plagiarisers are being found out. And we have the internet to thank for that.

Many poets are nervous about their work appearing on the internet. We're almost preconditioned to believe that someone is out there waiting to steal what we put out to public view. But in fact, the internet makes it harder for plagiarists, not easier. A poem placed in public view can always be matched with its real owner. A simple Google check (other search engines are available) is a standard tool in the competition judge's repertoire. It will pick up, not just plagiarised work, but also any other work that runs the risk of creating a copyright lawsuit by having been previously published somewhere else. Every competition I've judged has seen at least one entry disqualified from the shortlist as a result.

The Google check isn't perfect. There are any number of poems from the pre-internet generation which are not online, and which won't show up on a Google search. But a winner's name may well show up, once announced. Their past publication history may show up. And thanks to the dedication of poetry detectives like Ira Lightman (pictured), who brought the recent scandals to light, the plagiarists will soon run out of places to hide.

There must be more than a suspicion that the plagiarism scandal calls into question the whole existence of poetry competitions. When a brilliant, unknown poet appears from nowhere to walk off with several hundred pounds' worth of prize money, some are bound to look askance on the winner and wonder just how original they really are. Are they just passing off the work of forgotten writers from a generation earlier? There are certainly rumblings that some competition organisers are going to start looking with new suspicion on ‘unrecognised’ names who achieve competition success.

To me, this is a dangerous mindset. After all, the whole point of poetry competitions is to give the brilliant unknowns a chance to make their mark, on a level playing field when up against established names. That's why poetry competitions are judged anonymously – so there's no chance of a judge being influenced by an entrant's reputation, or lack of one.

There are already competitions which churn out the same ‘type’ of winner, year after year with tedious predictability – often a winner who turns out to be a well established name on the poetry scene, frequently someone with several collections to their name. It's almost as if the judges only want work from a particular school of thought or writing. It would be depressing indeed if those competitions which still champion the independent voice are put in a position where they can no longer do so. Small competitions don't have the funds to defend lawsuits, and can't afford the reputational damage that might ensue if their champion work turns out to have been a plagiarised product. Will these competitions close altogether, rather than run the risk?

I'm a competition judge myself. I certainly don't want to be in the embarrassing position of mistaking a plagiarised poem for a brand new piece of original writing. But it could happen, even to the best of us. The sad fact is that many poets of the last hundred years have published their collections and then vanished without trace – and there's nothing to stop an opportunist taking advantage of the words they left behind them. Not even the best read judge is going to be able to recognise every plagiarised work for what it really is.

However, there's just the possibility that the recent scandals are signs that the situation is getting better, not worse. Serial plagiarisers are being found out. And we have the internet to thank for that.

Many poets are nervous about their work appearing on the internet. We're almost preconditioned to believe that someone is out there waiting to steal what we put out to public view. But in fact, the internet makes it harder for plagiarists, not easier. A poem placed in public view can always be matched with its real owner. A simple Google check (other search engines are available) is a standard tool in the competition judge's repertoire. It will pick up, not just plagiarised work, but also any other work that runs the risk of creating a copyright lawsuit by having been previously published somewhere else. Every competition I've judged has seen at least one entry disqualified from the shortlist as a result.

The Google check isn't perfect. There are any number of poems from the pre-internet generation which are not online, and which won't show up on a Google search. But a winner's name may well show up, once announced. Their past publication history may show up. And thanks to the dedication of poetry detectives like Ira Lightman (pictured), who brought the recent scandals to light, the plagiarists will soon run out of places to hide.

Monday, 10 June 2013

Iain Banks: RIP

It's perhaps a tad unusual for a poetry blogger to be writing a memorial to the life of one of the UK's most unusual prose writers. But the sad loss of Iain Banks, who died on 9th June aged 59, has got me thinking about why the poetry I write sounds the way it does. The man's influence got into my writing, I think, more deeply than I ever realised.

I've been obsessed with stories and storytelling all my life, from long before I ever started writing poetry. There was a rather fantastical element to my favourite reading matter – fairy tales, Victorian novels, and Tolkien – and I have to confess that when I was younger I pretty much avoided contemporary fiction altogether. I was writing, all this time: fairy stories of my own, some of them of epic proportion. I used them as allegories – spaces where I could get to grips with the darker aspects of the world around me, to try to make sense of the struggles of the people I loved. I've always believed, as Tolkien did, that mythic storytelling is anything but escapism. It is full of symbolism, allusion and metaphor, a way of looking slant-wise at the world and of setting its tragedies and pains in a wider, more universal context.

It was rather a shock to the system to discover a contemporary writer who set his tales in the modern world, but had a way of telling them that was utterly faithful to the tradition of mythic storytelling with which I'd fallen in love. The BBC dramatisation of The Crow Road in the 1990s was my first encounter with Banks's quirky storytelling (I still maintain that “It was the day my grandmother exploded” is the greatest opening line in English literature), and I was captivated from the outset. There was an epic quality, not just about the sweeping Scottish landscapes of the story, but about the young hero's classic quest (in this case, to uncover the truth about the mysterious disappearance of his uncle some years before, opening up all kinds of dark family secrets on the way). The mixture of folklore and pop-culture which seasoned the story was an intoxicating combination for me. And for the first time, it made me realise that it was possible to tell a timeless tale in entirely modern language.

And that, really, is what I've been trying to do in my writing ever since.

Iain Banks was more than a cracking good storyteller, though. His descriptive writing was some of the most beautiful I’ve ever read, in prose or poetry. There was something of the nature poet in Banks’s writing, a knack of capturing a place in a way that engages every sense. The opening paragraphs of Espedair Street, his roller-coaster faux-biography of an ageing, forgotten rock star, have haunted me for years:

“Two days ago I decided to kill myself. I would walk and hitch and sail away from this dark city to the bright spaces of the wet west coast, and there throw myself into the tall, glittering seas beyond Iona (with its cargo of mouldering kings) to let the gulls and seals and tides have their way with my remains... or be borne north, to where the white sands sing and coral hides, pink-fingered and hard-soft, beneath the ocean swell, and the rampart cliffs climb thousand-foot above the seething acres of milky foam, rainbow-buttressed.

“Last night I changed my mind and decided to stay alive. Everything that follows is... just to try and explain.”

My own nature writing harks back to similar scenes – the shore, the deep ocean, even the Corryvreckan whirlpool (which also makes an appearance in that first paragraph) – and I've always tried, like Banks, to convey a sense that my reader is right there in that place, in the snapshot moment, smelling and tasting the tang of wind and sea-spray. I'm surprised now, when I revisit his prose, just how many echoes of him I find in my most recent poetry.

Tastes and tangs and the crazy soundscapes of life infuse Banks's descriptive writing. It's hardly a surprise. Banks was a malt whisky enthusiast of the highest order. He knew the spirit's capacity to surprise and astonish with its spectrum of flavours and fragrances. He also knew the futility of trying to pin down the character of a malt whisky. His non-fiction bestseller Raw Spirit wasn't really a "search for the perfect dram", despite the advertising slogan: it was an autobiographical road trip, a journey of self-discovery. That heightened capacity for sensory detail, honed through a finely trained whisky palate, was a gift that any poet would envy.

There's a Gothic aspect to Banks's novels which made it very easy for me to fall in love with them after an upbringing on fairy tales and Victoriana. The macabre murders in Complicity (the first Banks novel I read cover-to-cover) almost have something of the Brothers Grimm about them; the islands and open spaces and creaking ancient buildings where his stories are set could easily belong in the work of the Brontës or Bram Stoker. Banks's characters have secrets, personal tragedies, enormous unspoken sadness, which make them grotesque and compelling at the same time. They are the sort of characters I have been trying to fathom out in all my writing, from my first teenage epics to my most recent prize winning poems. But it's his eye for the small details which make their awful dramas resonate. In The Steep Approach to Garbadale, a dream-like fixation with the description of an old coat becomes a chilling foreshadowing of the wearer's suicide:

“The coat is too big for her, drowning her; she has to double back the cuffs of the sleeves twice, and the shoulders droop and the hem reaches to within millimetres of the flagstones. She rubs her hands over the waxy rectangles of the flapped external pockets... The door slams shut behind her, leaving him where he's been for some time now, screaming unheard at her, silently and hopelessly, begging her not to leave.”

What I love most of all about Banks, though, is that his writing bursts with an unstoppable compulsion to tell stories; and it's that compulsion that makes the tales so vibrant, so addictive. The plots may be fantastical, the settings might read like something from Robert Louis Stevenson or Daphne du Maurier, but they're infused with satire and social comment which brings a realness to them despite the preposterous excesses of their characters. If Banks ever guest-featured in one of his own novels, for my money it was in the guise of Kenneth McHoan, the storytelling father of The Crow Road – the curmudgeon with a romantic streak, blasted off the face of the earth by a lightning bolt on a church roof, leaving the memory of endless tall tales behind:

“ 'The rich merchant was very powerful, and he came to control things in the city, and he made everybody do as he thought they ought to do; snowball-throwing was made illegal, and children had to eat up all their food. Leaves were forbidden to fall from the trees because they made a mess, and when the trees took no notice of this they had the leaves glued onto their branches... but that didn't work, so they were fined; every time they dropped leaves, they had twigs and then branches sawn off. And so eventually, of course, they had no twigs left, then no branches left, and in the end the trees were cut right down... Some people kept little trees in secret courtyards, and flowers in their houses, but they weren't supposed to, and if their neighbours reported them to the police the people would have their trees chopped down and the flowers taken away and they would be fined or put in prison, where they had to work very hard, rubbing out writing on bits of paper so they could be used again.'

“ 'Is this story pretend, dad?'

“ 'Yes. It's not real. I made it up.'

“ 'Who makes up real things, dad?'

“ 'Nobody and everybody; they make themselves up. The thing is that because the real stories just happen, they don't always tell you very much. Sometimes they do, but usually they're too... messy.' ”

I have to leave this tribute on that thought – and with the awareness that the world has lost one of its most original and idiosyncratic storytellers, a poet in his own outlandish way. The great man is away the Crow Road; and may the journey ahead be a bright one.

Monday, 20 May 2013

A long way to fall?

It's finally happened. After years of submissions to magazines and competitions, many rejection letters, occasional acceptances, and the odd envious glance at my younger, better looking, more successful friends in the poetry business, I finally have a book of poetry to my name.

It's been a rapid journey from acceptance to print – 3 months to correct the manuscript of A Long Way to Fall, gather in endorsements, and get the finalised version printed and bound. But that's not to say that the process of producing the book has been a rapid one. My initial query to the publishers was submitted a year ago. That was after half a dozen years putting together prototype versions of the collection, trialling different combinations of poems to try to find a harmonious whole. Then there's the time it took to produce the poems themselves – seventeen years since I first started writing poetry. It has taken about as long to create my debut collection as it takes to mature the most famous expression of my favourite Ardbeg single malt. As one who believes that poetry and whisky have a lot in common, I'm not altogether displeased by the comparison.

As it happens, there aren't any poems in A Long Way to Fall which date back quite that far. The oldest poem in the collection was written in 1999, though it has undergone a few changes since then. The newest pieces? Mere months old – babies by comparison.

The collection might never have seen the light of day were it not for the support of a select group of fellow poets. Two of them – Ann Heath and Tanya Nightingale – are still without a debut collection to their name: a serious deficiency that I hope the poetry world will remedy soon, because the best of their writing is amongst the best poetry I've read anywhere, ever. Ann and Tanya were in on the story right from the start. Not only did they offer some invaluable critique of individual poems, but they helped enormously in the selection and ordering of material. It is thanks to their insight that I was able to figure out the eventual shape of the collection, the sequence and flow of the poems, and – crucially – which poems to put in, and which to leave out.

Just over half of my 50-odd previously published poems made it into the collection. So what about the poems that weren't included? Some of them were immature pieces. They got picked up by editors in my early days, when I submitted a great mass of work all over the place. It was a great encouragement to get these accepted for publication, and I'm proud to have them on my CV. But if I'm honest, I probably wouldn't write these poems the same way if I were writing them now.

Other poems were left out, not because I was unhappy with them, but because they didn't gel with the overall feel of the collection. I decided with some sadness that I wasn't able to include my first ever competition-winning poem, Joni Melts Wax in a Saucepan. It isn't rubbish – the cheque it earned me back in 2004 testifies to that – but its style and voice are very different from the rest of the material in the collection. Joni is light-hearted, satirical, and really a much 'fluffier' poem than anything else in the collection. It may well belong in a future compilation, though, one with a slightly different mood to it.

The remainder of the poems in the collection are hitherto unpublished. They include a whole set of more recent poems which really created the distinctive 'voice' of the collection. They dictated the ebb and flow of material, the pace and style of poems which went together, the vital balance between lighter and more serious material. Once these were included, the other poems fell into place.

The process of getting A Long Way to Fall into print has been a voyage of discovery. At times I've felt like the seafaring character who appears in several of the poems: adrift on uncharted seas, never quite sure where I'll end up. But the book is here now. Finally, I am a Proper Published Poet. And here, I'm beginning to discover, is where the journey really begins.

A Long Way to Fall is available now from Lapwing Publications (email lapwing.poetry@ntlworld.com), price £10. ISBN 978-1-909252-40-0.

Thursday, 18 April 2013

Poetry Transvestism, Part 2: are you Sounding Lyrical?

Recently I had the privilege of taking part in the inaugural concert of the Sounds Lyrical Project – a collaborative venture between a group of poets and a small team of classically trained composers who have set our poems to music. I've always loved classical recitals, and for the Project, a full-length evening concert of original work was a "yes we can" moment: it was proof that the concept of Sounds Lyrical has something going for it.

Recently I had the privilege of taking part in the inaugural concert of the Sounds Lyrical Project – a collaborative venture between a group of poets and a small team of classically trained composers who have set our poems to music. I've always loved classical recitals, and for the Project, a full-length evening concert of original work was a "yes we can" moment: it was proof that the concept of Sounds Lyrical has something going for it.But all of us, composers and poets alike, are aware that the Project won't get very far if we stick to this format.

A number of things struck me about the audience. One, there weren't all that many of them. Okay, fair enough – I've performed poetry to smaller crowds. What matters isn't so much the number of people turning up, but the quality of the experience they have when they do.

More striking than the numbers attending, though, was the proportion wearing what I would describe as "smart dress". Jackets and college scarves were the order of the day. Heck, I wore a jacket and college scarf. There was a practical reason for this (we were performing in a freezing cold chapel – why does this seem to be a recurring theme of my poetry gigs?!). But I was acutely aware that this isn't how I normally dress when I'm performing poetry. Jeans and T-shirt are more my style.

I don't think the audience were any posher than the crowd that used to turn out to hear me MC at Speakers' Corner. But there's clearly a feeling that a classical concert is a "special occasion" and requires a slightly higher standard of decorum than the average open mic. The need to dress smartly, to sit perfectly still for two hours in a cold chapel, not to shuffle feet or to cough, was clearly in evidence. Maybe this is the reason that concerts of this type (not to mention poetry readings of this type) tend not to attract large audiences?

The conversation at the pub afterwards explored this issue. One of the reasons the project was set up in the first place was to tackle an image problem within contemporary classical music. The intellectual elitism of Schoenberg and the European avant-garde, according to my composer friends, have done for modern composition what the pretentious poets of my recent blog post have done for contemporary poetry.

But, in composition at least, intellectualism is now on the wane. Composers these days, by and large, want to collaborate – to fuse genres and styles, to pick and mix from a melting pot that includes rock, jazz and world music as well as the European classical tradition. The opportunity to work with artists across a range of media also presents the chance to bring new music to audiences who wouldn't ever do the wear-a-jacket, sit-in-a-cold-chapel thing.

The ideal venue for our concert might well have been the pub we adjourned to afterwards. Not that we'd have wanted to ambush unsuspecting punters with a resonant baritone and the nifty fingerwork of a skilled professional pianist; but there was actually a piano in that pub, and no particular reason why the Project couldn't make use of it at some unspecified future date.

The advantage of "doing art" in an unconventional venue – a pub, cafe, railway station, or wherever – is that it opens up the art to people who wouldn't otherwise take a chance on it. Effort is needed to put on a jacket and sit in a cold chapel; but if you’re anything like me, you won't need all that much persuading to come along to your regular pub and stump up the price of an extra pint or two to try out something just a bit different. Especially not if beer, conversation and good company can all still be enjoyed into the bargain.

So where now for Sounds Lyrical? Our lead composers have been adventurous with their material, and in choosing to collaborate with an unruly group of poets. We need to be equally adventurous as to how and where we present that material. There are plenty of possibilities. When we lived in Birmingham, my wife and I sang in a choir who did more gigs in pubs than in concert halls. Their repertoire ranged from Britten and Barber to Abba and Queen (not to mention some extraordinary original compositions from members of the choir themselves). Their concerts were fun, accessible, and very different to any recitals I've ever attended.

This is the sort of model I would like Sounds Lyrical to aim at. I love to see poetry invading the public consciousness by showing up in unexpected places. And I'd love to hear modern classical music do the same.

Sunday, 31 March 2013

Poetry transvestism?

It's not all that long ago that I was blogging about the possible demise of the York Literature Festival - one more victim of an austerity regime that seems to place little value on the power of the creative arts. Thankfully, the Festival has survived. This year it recorded its most triumphant season yet, with over 2000 tickets sold for a variety of shows ranging from big-name gigs to smaller community arts ventures. There was a veritable buzz about the Festival this year - ample proof that all that energy, enthusiasm and creativity has not been in vain.

One thing that struck me very forcefully about this year's Festival was the capacity for poetry to manifest itself in all kinds of guises that one wouldn't automatically think of as poetry. It crept up on this year's audiences in other guises - wearing the clothes of other artforms, if you will, a sort of literary transvestism.

It manifested itself most clearly in this year's headline act - a double-header, featuring on the one hand a fairly conventional poetry reading by the Poet Laureate herself, Carol Ann Duffy, and on the other a sublime fusion of classic verse with rock 'n' roll in the guise of poetic troubadours Little Machine. Little Machine are a couple of 90s stadium-rock survivors who have teamed up with a performance poet to present several thousand years' worth of poetry - from Sappho through Shakespeare to Philip Larkin's infamous "This Be the Verse" - in a variety of infectious musical arrangements. Some were sublime, some ridiculous, but all were calculated to get right under the skin and leave you humming along. When they handled classic texts, they had the gift of breathing new freshness into words which were otherwise over-familiar, giving them a whole new lease of life. When they set contemporary verse, they created a whole new way of approaching an art form that is all too easily dismissed out of hand as too serious, too difficult, or too intellectual. The great joy of Little Machine is that they showed just how wrong this stereotyping of poetry can be.

Little Machine aren't the first musicians to do this, of course. Last year I had the great pleasure of seeing my personal folk-rock heroes, The Waterboys, electrify the stage with a concert performance of An Appointment with Mr Yeats, an entire album's worth of musical settings of the poetry of WB Yeats. And if Little Machine surprised and delighted, the sheer power of the Waterboys' rendition of The Hosting of the Shee was enough to blow you backwards off your chair.

Poetry and music, of course, go hand in hand as art forms. An even more intelligent form of poetic transvestism took place in the form of Bob Beagrie and Andy Willoughby's show Kids: a poetry cycle ostensibly inspired by the film reel of Charlie Chaplin's silent classic, The Kid, but underpinned fundamentally by the writers' experiences of working with deprived and troubled teenagers in the most recession-hit areas of north-east England. The power of Kids came not just from the words, the mimes that accompanied them, and the excerpts from Chaplin's original movie that played out as the backdrop to the show (to the accompaniment of a brand-new piano score). It came, most of all, from the quiet anger of the social commentary that infused each poem. This was poetry in the form of an art that wasn't afraid to challenge the status quo, and ask the big questions of how and why society has ended up in such a mess, and what are we going to do about it?

I'll even admit to having a go at a bit of poetic transvestism myself. Telling the Fairytale, my first ever show for the Festival, wasn't really my show at all, if I'm honest: it was a collaborative effort between me and my good friend, storyteller Helen M Sant, to recreate some classic pieces of folklore and re-tell them in a 21st century context. In some ways, Telling the Fairytale was the exact opposite of Kids. Instead of contemporary social comment, here we had timeless fairy stories. Instead of a Powerpoint projector and a piano, our backdrop was an icy cold, medieval gothic church. But the reason I love fairy tales lies in the layers of imagery and metaphor behind them. The archetypes of fairy story may hark back to a bygone age, but they represent real concerns. Love, abandonment, social disconnection, mental illness - and the ultimate need we all have, for that happily-ever-after. Being able to wrap these concerns in the cloak of familiar childhood stories provides a way in for an audience, where a direct approach to the subject in a poem might be hollow or trite. Being able to perform these poems, set against some wonderful contemporary storytelling and a haunting flute accompaniment, made an hour of sheer enchantment.

It seems that rumours of the death of literature in York have been very much exaggerated. It's well and truly thriving, and often in the most unexpected guises. All art is richer when it collaborates, when it draws from experience beyond itself. And poetry, perhaps, most of all.

So that's my challenge to poets for 2013. Try on someone else's clothes for size, and see how they feel. An artist's, a musician's, a social campaigner's. You could find a new freedom in your writing. And, perhaps most importantly, you might find new audiences too.

Sunday, 10 March 2013

Pretentious poets

I'm not convinced that performance poet Tim Ellis will thank me for name-checking him at the start of a blog post headed "Pretentious Poets." But it's thanks to him that I'm writing this post. Tim and I have different poetic backgrounds and interests, which has made for some lively online debates in the past couple of years. While we often disagree about specifics, we mostly keep a healthy respect for the other's point of view.

But I cannot, ever, agree with Tim that the work of TS Eliot deserves to be consigned to the poetic dustbin.

I should add that Tim is one of the least pretentious poets I've ever met. As a writer he's a genius of rhyme and rhythm; as a performer, he was a worthy winner of the 2011 York Poetry Slam, for which I was part of the judging panel.

As I understand it, Tim's take on TS Eliot is this. TS Eliot is a pretentious poet. Much of his work is so thick with obscure allusions to ancient Greek and Roman civilisation that it's impossible to find a way into it unless you have a higher degree in classical literature. And, surely, any poetry that is this hard to understand just adds fuel to the argument that poetry is something that's disconnected from reality, and simply not worth bothering with.

I have a lot of sympathy with this argument – and it's one that has made me think about why I first started writing poetry. I came to poetry relatively late in life, following teenage years filling bookshelves full of ring binders with really bad novels of epic proportion. My poems started life as stories that I was trying to tell: some to fathom out the problems of the world or the complexities of the people around me; others, simply to capture the mood on one particular day or in one special place. "Art", for its own sake, was practically non-existent in my list of priorities.

Accessibility is always really important if you're trying to tell a story. And it's the same with my poetry. If people don't get what my poems are going on about, then on some level the poem hasn't worked.

The trouble is, other poets don't write for the same reasons that I do. There are many who write for no other reason than the joy of artistic expression. They don't necessarily need an audience; and when they get one, it may not matter if not everyone in the audience can understand what they're going on about.

Which brings me back to TS Eliot. His approach to poetry was in many ways the polar opposite of mine. Yet, when I blogged awhile back about "The Ten Poems that Changed my Life", The Waste Land was one of the poems I listed.

There is something magical for me about this poem. Eliot's ability to draw scenes and atmospheres, to get deep into the guts of his characters' (and his readers') dreams and fears, and the sheer musicality of his free verse – all these things weave a sort of spell about me. It doesn't matter that three-quarters of the classical allusions go straight over my head. Somehow The Waste Land bypasses my head and echoes inside my gut in a way that few poems have ever done.

Four Quartets, by contrast, leaves me cold. The layers of classical and artistic reference are so thick here that to me they're completely impenetrable. There's nothing I can latch on to or identify with. The atmospheric quality of The Waste Land is missing, the rhythm and musicality of the words seem to be lacking too. Its philosophising is abstract, self-indulgent. It makes no connection with me and sheds no light whatsoever on the world around me.

There seem to me to be a lot of poets who have been encouraged to write in a way reminiscent of what Eliot does in Four Quartets. The end result is to daze the reader with intellect. This can be done very cleverly; even though I don’t understand the end result of Four Quartets, I can at least tell that there's a master craftsman at work. Mostly, though, it just seems insufferably smug.

If there is a huge intellectual hurdle to be overcome before you can appreciate poetry, to me it is not good poetry, no matter how many awards it wins. Outside the rarefied atmosphere of literary circles, the misconception that 'serious' poetry is something too snobbish for the average man or woman in the street is still one that's all too common. And any poet dead set on propagating that misconception is going straight into my personal rejection bin. They're not telling a story. They're not even enchanting their readers with a glimpse of a dream. To put it bluntly, all they are doing is showing off how clever they are.

I'm really, really proud that there so many good poets on the Yorkshire scene who show that it is possible to be serious about your poetry without it becoming pretentious. The poetry world doesn't need another TS Eliot; one is quite enough, thank you very much. If a few regulars in the learned poetry journals could learn to be a bit less TS Eliot and a bit more Tim Ellis, they'd be doing all of us a favour.

Sunday, 17 February 2013

The Poetry Society: do we really need it?

I want to tell you about one of my new year resolutions for 2013. I'm going to join the Poetry Society.

I want to tell you about one of my new year resolutions for 2013. I'm going to join the Poetry Society.I have to admit to being rather cynical about the Poetry Society. Don't get me wrong – I like the idea of the Poetry Society. Goodness knows, poetry gets precious little promotion in the UK and it needs somebody fighting its corner. But does what the Society offers really justify a full membership fee, at current rates, of £42 a year?

Currently on offer in the membership package are: 4 issues of the society's broadsheet Poetry News (and the chance to submit your own poetry to be published in it); 4 issues of the premium poetry journal Poetry Review; discounts on critiques and appraisals from professional poets; 2-for-1 entry to the National Poetry Competition, which the Society administers; access to the Society website to promote your events and publications; and discounts on Poetry Society events, including products and masterclasses at the Poetry Café in London.

In many respects the Society does pretty good work. Their website (and especially the "Poetry Landmarks" section which lists places of interest to poets region-by-region, including regular performance venues) is a little treasure trove. The network of regional groups, or "Stanzas" (a name which is either poetically brilliant, or just plain pretentious, I can't quite decide which) provides a means for poets to meet, obtain constructive critique and develop and hone their work. The opportunity to promote yourself alongside the great and the good of the poetry world is one that no self-respecting self-publicist would want to pass up. And did I mention that the awesome Roger McGough is currently their president?

So what’s not to like?

Well, the poetry itself, for one thing. Some of the poetry that the Society promotes has what I can only describe as an image problem. To put it bluntly, a lot of people see it as unbearably pretentious. The poems that appear in Poetry Review and a lot of the pieces that win the National each year can be so sophisticated as to be pretty much inaccessible without a higher degree in literature. Many poets I know won't submit work to the Poetry Society for exactly that reason.

I have ambitions to be a serious poet, whose work is taken seriously. That's why I have finally decided to give the Society a try. But I'm still at the point where submitting my work to the National Poetry Competition feels like a waste of money. I simply don't write poetry of the intellectual intensity that seems to be required to make the shortlist. And even in my most serious, pretendy-strokey-beardy moments, I'm not altogether sure that that's the way I want my poetry to be.

As a dyed-in-the-wool Northerner, I have concerns about the London-centric nature of the Society. Sure, the Poetry Café is a brilliant thing. But it's in London. In fact, most of the Society's activities, and 90% of the stuff it promotes, is in London. The rest of the UK may well have the "Stanzas". But when I read the Society's literature, and look at its website, I still get the feeling that the provinces are just subsidising what goes on in London; and if I'm rarely in London, I'm unlikely to have the advantage of it.

I have a more fundamental reservation than these, though. My socialistic instincts don't sit easily with the fact that membership of the Society is solely by virtue of being able to pay for it. This is very different to, for instance, the Society of Authors where you're only admitted to membership once you have a bona fide publishing contract for your work.

I'm not advocating that the Poetry Society should have the same selection policy. Contracts to publish poetry are like gold dust (though not nearly so lucrative!), and any restriction of membership to poets who already have a published collection would raise a massive problem of elitism. But most learned societies require applicants to present some evidence of achievement in the field, and commitment to their continuing professional development. At the moment, all that Poetry Society membership signifies is that you're rich enough to pay the subscription. And as I'm forever arguing, the notion of poetry as a rich person's pursuit is probably the single biggest problem that our art has.